Jerry Lewis’s Infamous The Day the Clown Cried Will Finally See the Light of Day

The history of cinema is littered with films that were abandoned and/or unfinished for a variety of reasons, and subsequently left unseen by audiences. Dig into them, even just a little bit, and you’ll find fascinating “what if” scenarios, a sort of alternate film history of what might’ve been.

In 1933, producer Charlie Chaplin destroyed all known copies of Josef von Sternberg’s A Woman of the Sea for a tax write-off. Oley Sassone’s 1993 adaptation of The Fantastic Four was never screened; it was only made so that producer Bernd Eichinger could keep holding onto the film rights. Orson Welles abandoned The Deep in 1969 after encountering various production issues. (In 2015, the Munich Film Archive screened a version of The Deep created from work prints.) George Sluizer’s Dark Blood was almost finished when star River Phoenix died in 1993. (A rough cut played at film festivals in 2012, with Sluizer narrating the missing portions.)

And then there’s Jerry Lewis’s The Day the Clown Cried.

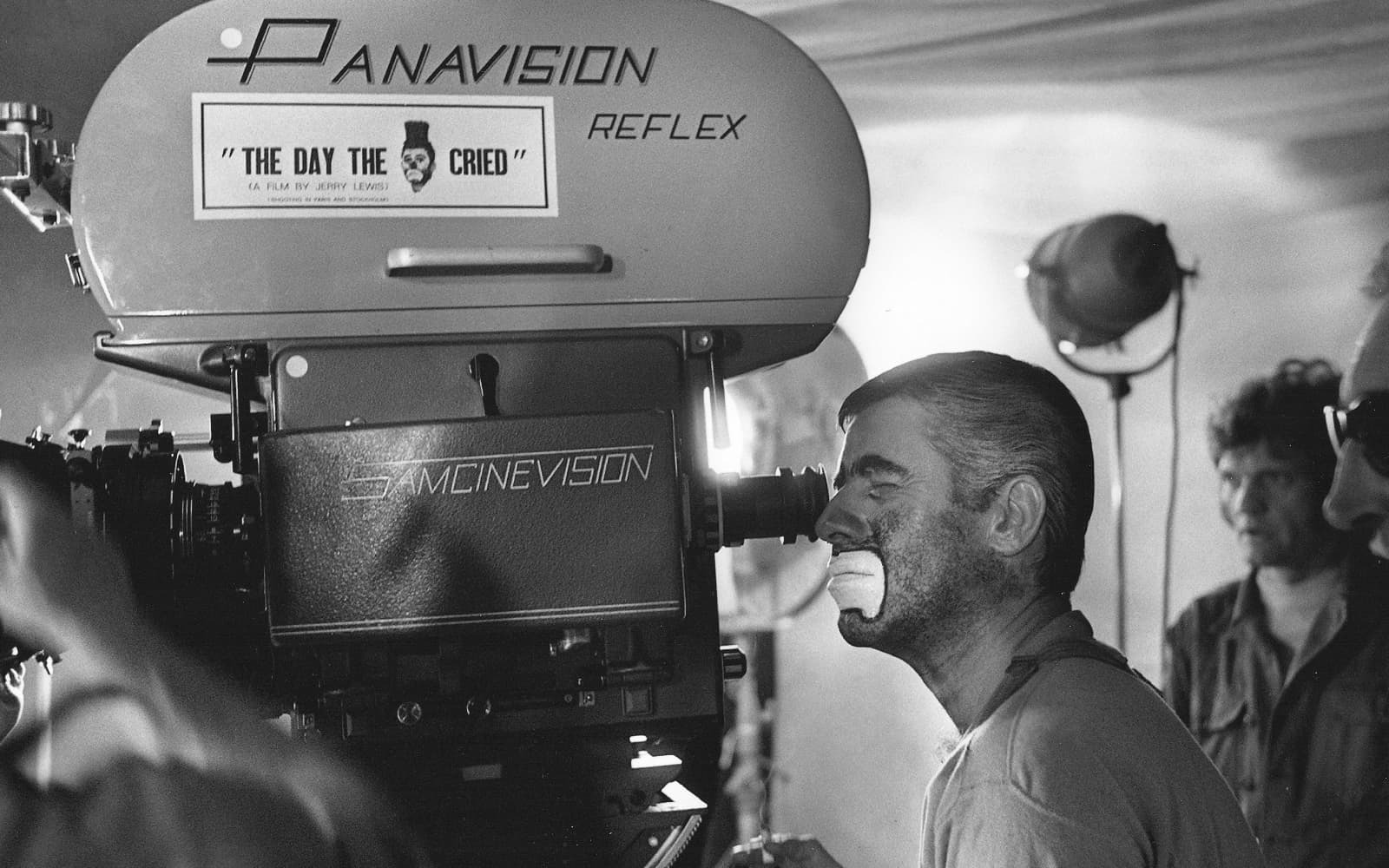

Written in the early ’60s by Joan O’Brien and Charles Denton, The Day the Clown Cried initially caught the attention of some big stars, including Milton Berle and Dick Van Dyke. But Jerry Lewis ultimately got the film as both director and star and began filming in 1972, only to run into problems from the get-go. Not only did producer Nat Wachsberger fail to adequately fund the film, but he’d actually lost the rights to the script after failing to pay O’Brien. Lewis eventually paid for the film out of his own pocket to the tune of $2 million, but after the film was finished, disputes between Lewis, Wachsberger, and O’Brien prevented it from ever being released. (The aforelinked Wikipedia entry has all of the details.)

Admittedly, production delays, funding issues, and contractual disputes are nothing new in film. What really propels The Day the Clown Cried to the heights of cinematic infamy is its premise: Lewis plays a disgraced German circus clown named Helmut Doork who’s arrested for mocking Hitler and eventually ends up in Auschwitz, where he’s forced to lure Jewish children to their deaths in the gas chamber.

By all accounts, Lewis set out to make a serious film about the horrors of the Holocaust and poured himself into the production. (He toured Dachau and Auschwitz, lost 35 pounds for his role, and claimed the film very nearly ended him in an interview with The New York Times.) The resulting film, however, has been roundly criticized by almost everyone who’s ever seen it.

In May 1992, Spy published “Jerry Goes to Death Camp!,” an oral history of The Day the Clown Cried that included interviews with folks involved in the production as well as some who’d actually seen the film. O’Brien, who wrote the film, called it a “disaster” while former Lewis staffer Jim Wright noted the significant changes that Lewis made to the script. Harry Shearer (This Is Spinal Tap, The Simpsons) described it as “drastically wrong” with “wildly misplaced” pathos and comedy.

Joshua White, who directed Lewis’s 1979 telethon, said the film’s dramatic scenes “were beyond [Lewis’s] range” and that Lewis “never really commits to the character. He’s always just Jerry.” Finally, Lynn Hirschberg, who had once interviewed Lewis, recalled her reaction to the film’s climactic gas chamber scene: “I was appalled. I couldn’t understand it. It’s beyond normal computation.” White summed up his feelings on Lewis and the film thusly:

When l saw it, I felt for him, because I could see him trying to clear the hypocrisy out of his life. He was always surrounded by sycophants, but he’d just gotten off Percodan, and he was very proud of that. Then to see this film that was so important to him and that was almost incompetent was just sad. He felt the world had conspired against him to prevent him from completing it. He endowed it with great sadness. It was “the lost film.” But it is so awful — you can’t even laugh at it. It’s so hopeless, you just don’t feel anything good for Jerry.

The Day the Clown Cried was not without supporters, though. French critic Jean-Michel Frodon saw a print of the film in the mid-’00s and praised its merits in comparison to other, more acclaimed — and more recent — Holocaust films like Life is Beautiful and Schindler’s List:

Jerry Lewis does not dance around the subject matter, the extermination of Jews by the Nazis, including the mass killing of children. A line of dialogue insists on this fact: “Children? You mean Jews!” This marks a radical difference with La vita è bella (Life is Beautiful, 1997) by Roberto Benigni. The Day the Clown Cried does not use the death camp as scenery in order to further dramatise a fable that could be just as well situated in any other detention facility. He openly confronts the Holocaust, with the only acceptable ending for a storyline in this context, no matter how perturbing it may be: death. This is exactly what Steven Spielberg carefully avoids doing in Schindler’s List (1993), preferring to tell the history of a genocide through the story of those who escaped it, in order to retain the sacrosanct happy ending.

Frodon was even more direct in an interview with Bruce Handy — the same Bruce Handy who, by the way, wrote “Jerry Goes to Death Camp!” back in 1992 — calling The Day the Clown Cried “a very interesting and important film” that was “brutally dismissed” by those who’d seen it.

For many years, Jerry Lewis was adamant that The Day the Clown Cried would never be released. Speaking at the 2013 Cannes Festival, Lewis expressed regret for having even made the film: “It was all bad and it was bad because I lost the magic… You will never see it, no-one will ever see it, because I am embarrassed at the poor work.” Which, of course, did nothing to diminish the film’s burgeoning cult status.

Indeed, the film’s forbidden-ness seemed only to increase people’s determination to experience it in some way. Clips have been uploaded to YouTube and Vimeo, only to be quickly removed. (Some behind-the-scenes documentary footage can still be found, though.) After he acquired a copy of the script, Patton Oswalt organized live readings with fellow actors and comedians until they were shut down by a cease-and-desist order. There were even some plans to remake the film with Robin Williams, which never came to fruition. (Williams would eventually star in another Holocaust-themed film, 1999’s Jakob the Liar, which was a critical and commercial failure.)

But now The Day the Clown Cried finally has a release date… sort of. Several years before his death in 2017, Lewis donated a copy to the Library of Congress with the stipulation that it not be screened before 2024. No specific dates have been announced, but a screening will finally take place later this year at the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center in Culpeper, Virginia. However, the film won’t be loaned out to other institutions and apparently, the Library’s copy of The Day the Clown Cried isn’t even a complete version.

At this point, though, that may be the best we can hope to ever get; the chances of a wider release are essentially nil due to the unresolved copyright issues that still surround the film. I suspect that The Day the Clown Cried is simply destined to remain in cinema limbo as a fascinating bit of film history whose reputation and infamy will forever eclipse the actual work itself.