Omer Mozaffar on Majid Majidi’s The Color of Paradise

Omer Mozaffar writes about of one of my favorite films, Majid Majidi’s beautiful and delightful The Color of Paradise:

In any case, “The Color of Paradise” does stand apart in one strange, distinct way from most every Iranian film I have ever seen. Should I find it perplexing that many films in this tenuously staunch theocratic state — including those from its own Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults — feature religion, but few films actually speak of the Divine? In a particularly pregnant layer of this film (which is incidentally more accurately titled, “The Color of God” or “Rang-e-Khoda”), the central characters long for and lash against the Divine, while peripheral characters segue themselves into superstitions. Through this thread, the film does seem to assert that our own narratives about the Divine also color our own pious aspirations. Thus, we wonder if, at the end of the film, there was reunion, and was that reunion depressingly sad or hopefully happy?

I still do not know. I am still peeling layers from the rose that is this film.

Mozaffar brings up a very interesting point: that a film like The Color of Paradise quickly and easily reveals the narratives and stereotypes that we use to evaluate and critique the films we watch.

The greater point that I am making, however, is that when we watch an Iranian film, we often view it through this lens: we assume that the film is heavy on social commentary. Some films — especially children’s films — indeed share sharp critiques, but some do not. Are the various females in a Panahi children’s film windows into Iranian gender dynamics? Are the absent domineering men in his films depicting the theocratic state? Perhaps. Here, is the broken nameless father in “The Color of Paradise” anything but a broken nameless father? Those questions are part of the nightingale’s journey, carefully peeling off the petals of the vibrant fragrant rose.

[…]

[S]ometimes we have the problem, the serious problem, of a prewritten narrative. I am speaking not of “narrative” in the sense of the story and plot in a specific movie. Rather, I am speaking about the way we imagine the world. These are the narratives we write in our minds in understanding a people. Our narratives often mix fact with fancy, legend with layers.

For example, those on the political right carry narratives about themselves that frequently speak of loyalty (to nation, to honor, to relationships); thus they depict the political left as disloyal. Those on the political left, however, carry narratives about themselves speaking of inclusion (of race, ethnicity, religion), implying that those on the right cling to a culture that is exclusive and excluding. Whether or not these narratives are accurate is not so much the point, for such narratives often have at least a shred of accuracy.

Rather, these narratives color our views of a people with such overpowering influence that they tint not only our interpretations of another people, but even our abilities to see their humanities. These narratives color our interpretations of movies, and even our acceptance of them. When we approach films through these narratives — through these preconceived notions — we might be blind to the colors, shades and textures before us.

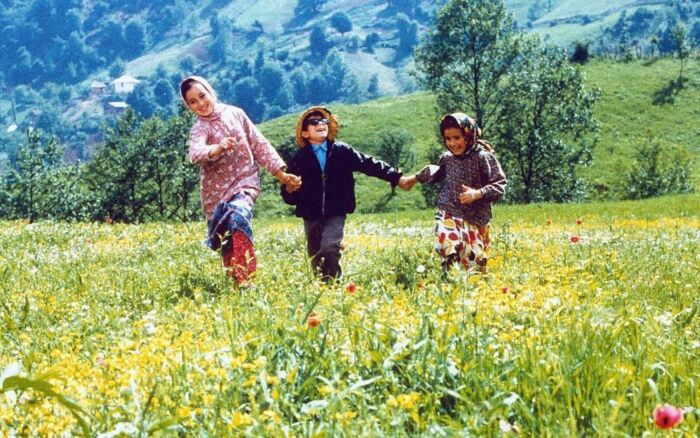

The Color of Paradise was one of the first, if not the first, Iranian film that I ever watched. And as I watched it, I found myself processing through certain stereotypes that I had regarding the country of Iran, even as I was caught up in the film’s breathtaking imagery. For example, I had always imagined Iran to be a dry desert place, and I was absolutely floored by the movie’s breathtaking scenery — dense forests, lush, verdant pastures, fields of colorful flowers as far as the eye could see. “Is that Iran?” my mother asked when I watched the film with her. I shared her surprise.

Thematically, the film also threw me for a loop. Prior to seeing any Iranian cinema, I had been under the impression that Iranian cinema was — as Mozaffar says — chock full of social commentary. And while there might be some commentary and critique in Majidi’s film — e.g., how society shuns and hides the disabled out of shame — the film is first and foremost a sort of magical realist film that is more in-line with, say, the films of Jean-Pierre Jeunet than Vittorio De Sica. (However, I don’t think Jeunet has ever made a film in which a character literally touches the face of God, but I digress.)

There are very few films that I feel I can recommend without any reservations whatsoever. Mozaffar’s article reminds me that The Color of Paradise is one of them. And if you don’t trust me, read Roger Ebert’s beautiful review.