My Cultural Diet for December 2023: The Boy and the Heron, Reservation Dogs, Godzilla Minus One

In order to better track my various cultural experiences (e.g., movies, TV shows, books, restaurants), I’ve created the Cultural Diet. Think of it as my own personal Goodreads, Letterboxd, and Yelp, all rolled into one (more info here). Every month, I recap everything that I watched, read, etc., in the previous month.

Given that Daniel James Brown’s The Boys in the Boat is one of my wife’s favorite books, it was inevitable that we’d see the movie adaptation in theaters. Directed by George Clooney, it’s a handsome and serviceable sports movie that hits many of the requisite tropes with its story about a team of underdogs who must rise above their differences and win the big championship — in this case, the 1936 Summer Olympics — for the sake of their country… and themselves. And insofar as that goes, The Boys in the Boat is decent enough. But it’s a surprisingly thin film, character-wise. A good sports movie gives all of the teammates moments to shine. The Boys in the Boat, however, focuses on just one of the titular boys (Joe Rantz, played by Callum Turner) to his teammates’ detriment. We learn little-to-nothing about any of them nor do we get any deep sense of their camaraderie, so there’s really no emotional investment in their struggles — or payoff for their triumphs.

Elf is one of those movies that feels impossible to review because of its position in our shared cultural consciousness concerning the Christmas season. We all know the story of Buddy the Elf, and his epic journey through the candy cane forest, the sea of swirly twirly gum drops, and the Lincoln Tunnel. Few actors have ever been so perfectly cast as Will Ferrell, though some of his antics are a bit less endearing now, twenty(!) years after the fact. But the movie’s true star is the North Pole’s immaculate production design, which perfectly captures the look and feel of those classic Rankin/Bass specials of my childhood. Here’s a fun bit of trivia: Terry Zwigoff (Ghost World) was originally offered the directing gig, but opted for Bad Santa instead. One can only imagine the alternate reality of a Zwigoff-directed Elf.

I didn’t realize until I had finished reading The Sky Vault that it’s actually part of a series. But Benjamin Percy’s novel is remarkably self-contained. Thus, I never felt like I was missing any important details or context while reading its story about a random assortment of people in Fairbanks, Alaska who get caught up in a secret government program stretching back to World War II, one involving bizarre weather phenomena and an otherworldly threat. Conversely, I don’t feel all that compelled to check out the preceding novels in Percy’s series or to eagerly await future installments. The Sky Vault contains interesting threads, including a conspiracy theorist whose theories finally become true, a former government agent-turned-mercenary in search of one final score, and an aging lawman caught up in events far beyond his ken. But the resulting novel is over-stuffed, and as a result, its core revelations about the aforementioned otherworldly threat are a bit undercooked. For what it’s worth, I was occasionally reminded of Peter Clines’ The Fold and Caitlín R. Kiernan’s Agents of Dreamland.

I feel a little weird trying to review Hayao Miyazaki’s latest because I think it’ll take another viewing or three to unpack it all. But I’ll say this: those expecting the whimsical fantasies of Ponyo or My Neighbor Totoro will be in for a shock. At first blush, The Boy and the Heron feels like Miyazaki’s most solemn film since 1997’s Princess Mononoke, one that’s almost nightmarish at times. Even though there are fantastical elements, like an army of giant parakeets and a hall of doorways that lead to other worlds, there’s something angry and unsettling beneath it all, starting with the protagonist: a sullen 12-year-old boy who grieves his mother’s death, resents his father’s new wife (who happens to his aunt), and is prone to self-inflicted injury. (And as for that army of parakeets, they eat people.) The story draws heavily from Miyazaki’s own childhood, so none of it feels random or haphazard, and the film’s climax is a very clear message from the director. Of course, being a Studio Ghibli film, The Boy and the Heron’s artwork and animation are absolutely gorgeous and immaculately detailed, outclassing everyone else with ease.

When I was in grade school, I was enamored with wilderness adventure stories, particularly ones set in the far north. While I read plenty of Jack London (e.g., The Call of the Wild), my favorites were Jack O’Brien’s Silver Chief stories, which chronicled the adventures of a Canadian Mountie and the titular wolf-dog (with some definite similarities to London’s stories). Reading Silver Chief to the Rescue now, I see why I loved it as a boy; O’Brien’s novel is filled with highly romanticized descriptions of life in the snowy Canadian wilderness that nevertheless ring with authenticity. (O’Brien was a surveyor on Admiral Byrd’s 1928 Antarctic expedition.) What I didn’t see as a kid, however, is the novel’s unvarnished racism. Native and Indigenous characters are often depicted in unflattering ways: as shifty, cruel, uncultured, and above all else, in desperate need of the White Man’s law. (And lest there be any doubt about that, the Mountie says as much in an extended speech.) At best, they’re useful and eager to serve the book’s protagonist. Even if you try and explain the book’s racism as a product of its time, it’s still pretty obvious and ridiculous.

I remember the kerfuffle that surrounded Fight Club when it was released back in 1999, with detractors calling it perverse and fascist. It was a box office powder keg, with many criticizing its darkness even as they missed the point of the darkness. An obvious issue with watching a film that was so controversial so long ago is the extent to which the ensuing years have dulled its edges or weakened its bite. Given that it’s almost 25 years old, some aspects of Fight Club do feel dated, like its MTV-esque flashiness. But its critiques of consumerism, capitalism, and advertising are perhaps even more relevant in today’s FOMO-driven and influencer-saturated world. The same could also be said concerning its depiction of Tyler Durden’s philosophy, which starts off with some valid points about modern masculinity but inevitably descends into dehumanization and nihilism. (Indeed, the film almost feels nigh-prophetic in light of the recent rise of incel culture and hucksters and cult leaders like Andrew Tate who can often seem very Tyler Durden-esque, albeit with none of Brad Pitt’s charisma or humor.) There’s the unavoidable irony of a big-budget Hollywood movie with major stars critiquing consumerism, but Fight Club has plenty on its mind that’s still worth considering, even now in 2023.

Back in the early ’90s, my friend Eric ran a bulletin board system (BBS) where I spent hours discussing music, anime, and video games with folks that I never met in real life. (It was an obvious precursor to the internet and I thought it’d be the coolest to run a BBS of my own. I never did, but I still wrote up documentation for one.) There was the thrill of connection, but also the thrill of danger and rebellion, particularly when you found documents with titles like “101 Ways to Wreak Havoc In Your School” that included instructions for all sorts of nefarious (and illegal) activities. Incredible Doom captures that sense of excitement as it follows several kids in a small podunk town who connect through a BBS, and become involved in the local DIY punk scene. But Incredible Doom isn’t just a nerdy celebration of technology; it’s also a bittersweet story of family trauma, first love, and the inevitable heartache that comes with realizing just how difficult it’ll be to hold on to your youthful idealism. I wish some of the series’ storylines had been explored a bit more fully, but if you ever spent any time on a BBS, making zines, and/or listening to punk/alternative music in the early ’90s, then I think you’ll feel like Incredible Doom was written just for you.

I must’ve seen Batman Begins at least three times when it was in the theater. As a comic book nerd, I was so thrilled to see a comic book movie that took Batman seriously, especially after the Joel Schumacher trainwrecks in the late ’90s. Drawing inspiration from Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One, Batman Begins chronicles Bruce Wayne’s initial efforts as the Caped Crusader after traveling the world to understand the criminal mind; as such, it’s suitably dark and stylish. Watching it now, nearly twenty years after its release, some parts definitely hold up better than others, though. Not surprisingly, Michael Caine, Gary Oldman, and Morgan Freeman are excellent in their roles, and I loved the believable manner in which Bruce acquires his fantastical Batgear. Unfortunately, Nolan edits the life out of his action scenes and at times, the film’s darker tone takes on a self-important air. Also, for all of the film’s realistic approaches to Batman’s skills, training, equipment, etc., we never do see how Bruce and Alfred deal with the massive amounts of toxic guano that would certainly fill the Batcave.

Reservation Dogs is usually billed as a comedy, but that doesn’t feel quite right. True, it’s frequently hilarious, albeit in a slightly skewed and often surreal way. But it’s also deeply sad as the ten episodes explore the effects of death on a closeknit community. Death of friends and loved ones, most obviously, but also the death of one’s dreams, of friendships, of innocence. Season two starts off a bit awkwardly as it tries to pick up where season one left off, but it’s also filled with delightful (and delightfully poignant) moments: Bear slowly maturing and getting a job; the reservation coming together to mourn and honor Elora’s dying grandmother; a group of middle-aged Indigenous women trying to hook up at a conference; or a couple of influencers imparting some “wisdom” to Bear, Elora, and the rest of the reservation’s youth. (I probably could’ve done without the catfish sex, though.)

Here’s the best way I can describe Takashi Yamazaki’s Godzilla Minus One, the 37th installation in the long-running movie monster franchise: it takes almost everything that’s beloved and celebrated about the Big G’s various incarnations, distills them down to their purest essence, and delivers a movie that’s filled with as much heart and conviction as it is kaijū spectacle. There’s none of the campiness that’s often associated with Godzilla movies, nor is there any cynicism or satire like 2016’s Shin Godzilla. Instead, it’s a deeply human and heartfelt story about guilt, sacrifice, and redemption that just so happens to also feature a giant lizard with atomic breath rampaging through post-WW2 Tokyo. Almost 70 years have passed since Godzilla roared onto the silver screen, and Godzilla Minus One is proof that he’s lost none of his potency as a cultural icon.

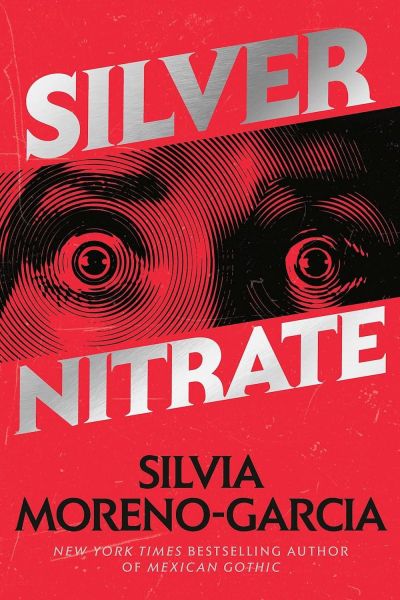

You don’t often read a novel that completely checks some of your boxes. But Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Silver Nitrate is one such novel for me. Obscure film history? Check. Eldritch horror? Check. Bizarre occult conspiracies? Check. Montserrat is a sound editor who, by virtue of a being a woman in ’90s Mexico, is constantly disregarded by her peers. But a chance meeting with a once-famous horror director might turn things around for her, especially after he invites her to participate in an arcane ceremony involving a lost film supposedly imbued with magic by a Nazi occultist. Naturally, things go wrong and Montserrat and her best friend — a former actor haunted by his reckless past — are soon visited by unsettling visions and forced on the run by an evil cult. Silver Nitrate drags in places and the protagonists’ nigh-constant bickering gets tedious, but Moreno-Garcia still casts a spell, especially when she delves into Mexican film history. Admittedly, I know very little about Mexican cinema, so I don’t know how much of Moreno-Garcia’s history is real or imagined — I was occasionally reminded of the mélange of conspiracy theories in Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum — but that just made Silver Nitrate all the more intriguing.